The great battle in 1863 was not the only time that soldiers occupied Gettysburg. As a National Military Park, the land was administered by the War Department for decades before becoming part of the National Park Service in 1933. As such, the department could use the land for whatever purpose was deemed necessary. During both World Wars the government made use of the historic landscape where Pickett’s Charge took place, and mandated the registration of monuments for potential removal as scrap metal for the war effort. The government saw the threats posed by 20th century warfare to outweigh the value of a preserved landscape.

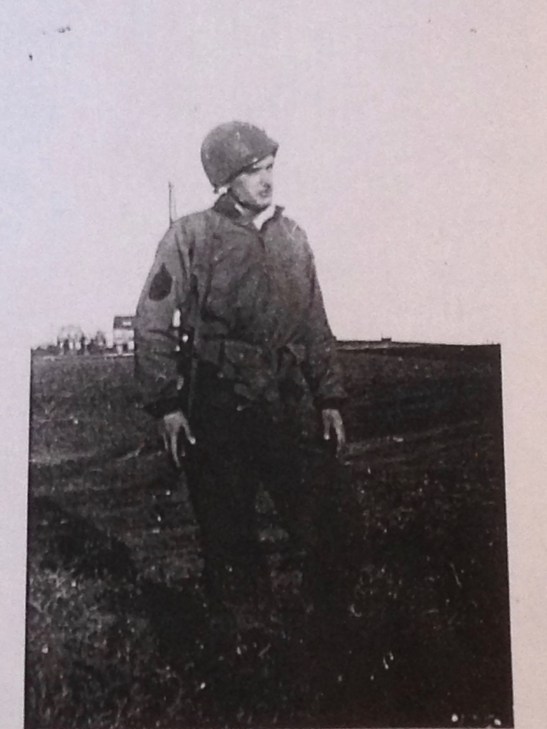

In 1917, the fields briefly hosted a mass mobilization camp, but that was short lived. The more major encampment came in 1918. The fields of Pickett’s Charge had become home to Camp Colt, a training camp for the newly formed Tank Corps. Soldiers under the command of Dwight D. Eisenhower ensured that the sounds of war again echoed through Gettysburg. Infantry carried out drill, and trucks with machine guns and 3 inch naval guns used the Round Tops for target practice. Once tanks arrived, drivers honed their skills on the battlefield, accidentally plowing through dirt as they maneuvered over historic landscapes, including the remnants of the Bliss family’s farm. After the war, the buildings were demolished, but the camp still left a physical mark on the landscape. Years later, William Redding, a farmer who had leased his farm from the government prior to the war, filed a complaint that, despite the fact the government had promised to return the land to the original condition, “sewers, water courses, trenches, and other excavations” remained in the fields.

In 1944, enemy soldiers again arrived in Gettysburg. Instead of invading Confederates, these new soldiers were German prisoners of war, mostly captured in North Africa. Chosen for the isolated location, local labor deficiencies, and remaining infrastructure, the former grounds of Camp Colt became home to an unnamed POW camp. Many Gettysburgians were angered by this, but not necessarily because of the use of the battlefield. Instead, their complaints primarily focused on fears of violent German escapees or anger that jobs vacated by their loved ones in the armed forces would be filled by the enemies the former workers had gone off to fight. These prisoners worked in businesses around Gettysburg, filling American soldiers’ vacant jobs by cutting wood, picking apples, and working in canning plants. Interestingly, many of the work crews also helped clear brush from the battlefield, helping to restore the historic landscape that their camp was intruding upon.

During the Second World War, Gettysburg’s landscape also paid a price during the scrap drives. Fences, markers, and even parts of monuments were split into categories based off “importance.” These categories would determine at what pace they would be removed if the situation became so desperate that the government absolutely needed the metal. Luckily, the situation never became so desperate to call for the removal of monuments, but Gettysburg did sacrifice “750 spherical shells, 14 iron guns, 1 bronze gun, 8 bronze howitzers, 26 bronze siege guns, and 38 bronze guns.” These were of post-Civil War manufacture, and deemed expendable. Modern visitors can still see the places where the spherical shells were once placed, such as the concrete foundations next to Cushing’s Battery at the Angle.

Ultimately, Gettysburg sacrificed parts of the historic and commemorative landscape during the World Wars. Fields were occupied by soldiers, weapons were discharged towards the Round Tops, military vehicles drove over previously preserved fields, and commemorative objects were removed for scrap drives. Were these sacrifices worth it? Should the government have found different places for military camps and different sources of metal, or was the integrity of Gettysburg’s landscape worth partially sacrificing in order to achieve military success? Imagine if modern prisoners from the War on Terror were brought to live on the fields of Pickett’s Charge today. During the World Wars, Gettysburg and the historical community were willing to consent to sacrifices for the war effort, but it is far less likely that these sacrifices would be accepted today.

Sources:

“Camp Colt Damages.” Gettysburg Compiler, May 1, 1926.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967.

Hartwig, D. Scott. “Scrap Drive 1942.”

Murray, Jennifer. On A Great Battlefield: The Making, Management, and Memory of Gettysburg National Military Park, 1933-2013. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2014).